Fall Art Auction · Sunday, September 28

Paintings · Prints · Beadwork & Weavings

Oil on Board.

SOLD $48,000

Etching with Aquatint

SOLD $26,000

Oil on Canvas (1896-1977)

SOLD $19,000

Oil on Canvas

SOLD $16,000

1912 Oil on Canvas

SOLD $15,000

Oil on Canvas

SOLD $13,000

Exhibited Oil on Board

SOLD $9000

SOLD $7000

Navajo Weaving

SOLD $6000

Chief's Blanket Design Weaving

SOLD $5000

Oil on Board

$5000

Oil on Board

SOLD $4800

Beaded Possible Bags

SOLD $4600

Lithograph

SOLD $4400

Modernism and Millenia

Centuries before the words “modern art” were spoken in America, Native peoples were portraying the world around them in elements of pure design that we now call abstraction. From beadwork and textiles to pottery, painted hides and sand paintings – abstraction was the essence of Native American art for thousands of years. The forms and motifs that were created didn’t seek to mimic nature. Instead, they portrayed mountains, rivers, animals, and spiritual forces in designs of geometry and rhythm. These anonymous indigenous artists across centuries, the majority of them women, would in various ways influence many mid-20th century American artists, mostly men.

The Kansas City artist Ron Slowinski, whose works are included in this auction, was greatly influenced by Native American art—particularly Hopi pottery and Navajo symbolism. These influences are notably visible in his Hopi Flower and Pollen series, both of which translate Indigenous themes into abstract expressionist paintings.

One of the more interesting examples of Indigenous influence on American art is the story of Jackson Pollock. Growing up in Arizona, Pollock observed Native traditions first hand and often visited the Southwest Museum of the American Indian where he developed a deep respect for Native art and custom. But the most important discovery came in 1941 when he visited the groundbreaking Indian Art of the United States exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art where he watched Navajo medicine men creating sand paintings. Working in a trance-like state, they stood over their art pouring colored sand into intricate, geometric designs. Pollock returned repeatedly to watch them work. He later acknowledged that their approach to painting influenced his own drip-painting method. Previously an easel painter like everyone else, Pollock said of his most famous technique, “On the floor I am more at ease… This is akin to the method of the Indian sand painters of the West.”

Artists like Jackson Pollock and Ron Slowinski were formally educated in art and history. Their inspirations sprang from this and other experiences, while American Indian artists were compelled more organically. They knew only a worldview where plants, animals, and geological features were considered relatives and spiritual beings. Their artistic expressions sprang from their deep, immersive spiritual connection to the living, interconnected system of the natural world.

Expanding on Sandzen

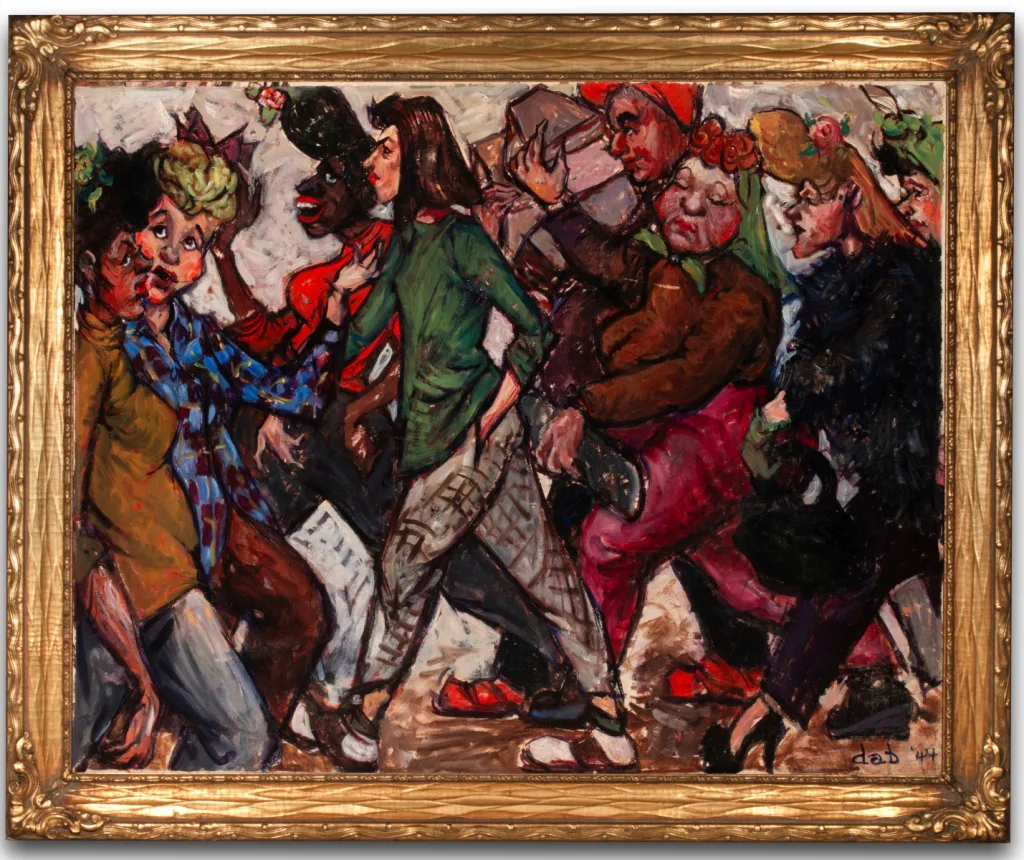

Trousers and Taboo

With the title of her painting Witches in Britches Dorothy Bartholemy seems to invite us to think of a different B-word, one that rhymes with britches, when considering the audacity of the women she portrays in the year 1944. Nevertheless, Witches is the word she uses to refer to the cadre of gals in her composition who, like witches in times past, were perceived as suspect, nonconforming and fearsome. At the same time, she gives us satire and humor that flows free through her work, including even the expressive brushwork she used to set the scene. The scene she creates chips away at taboos and it challenges the rules imposed on women in 1944 while avoiding anger or meanness.

High-waisted Trailblazers

In the 19th century and early 20th century, pants were widely considered men’s wear, and women who donned them risked ridicule—or even arrest. Women like Amelia Bloomer advocated for “rational dress” as early as the 1850s, introducing loose trousers (later called bloomers), but these never caught on broadly and were quickly relegated to reformist oddities.

Even into the 1920s and 1930s, pants were still largely taboo for women in public settings. A few fashion-forward women challenged this. Marlene Dietrich and Katharine Hepburn famously wore trousers in Hollywood, sparking admiration and scandal. Coco Chanel promoted sporty trousers for resort wear as early as the 1920s, though mostly for women of the leisure class while on vacation. For the average American woman, wearing pants was confined to private life—if at all.

Enter Rosie the Riveter and Katherine Hepburn

World War II was the true inflection point. With millions of men drafted, American women entered the workforce in unprecedented numbers. In factories, shipyards, and other war industries, trousers became a matter of practicality and safety. Slacks, coveralls, and dungarees were necessary to operate machinery and perform physical labor. Rosie the Riveter, the iconic figure of female war labor, was always pictured in trousers—often rolled-up work jeans, sometimes even coveralls. The necessity of this new workwear normalized the sight of women in pants—not just in factories, but in public spaces during wartime. Women wore them on the way to work, in shops, even in restaurants. And for the first time, trousers were mass-produced and marketed specifically to women.

At about this same time, Katherine Hepburn wore high-waisted slacks and wide-legged trousers as part of her daily wardrobe, both on-screen and off. Around the lot, she refused to conform to studio expectations for feminine dress, reportedly walking around in men’s slacks when off duty—even when asked not to. This and her general demeanor had led to her being labeled box office poison in the late 1930s.

The War Ended. Not the fight

After the war ended in 1945, it was presumed and expected that women and other minorities would drop back to pre-war positions. But for women at least, the genie was out of the bottle. Even though just a little over a decade earlier a woman had been arrested for wearing pants in a Texas courtroom, by the 1950s, women’s trousers were being widely marketed as casual and leisure wear. Capri pants and pedal pushers became fashionable, especially among younger women and suburban mothers. The genie was definitely out of the bottle. In fact, in the 1960s sitcom, I dream of Jeanie, Barbara Eden wore billowy pantaloons on television, albeit high-waisted because censors forbade her navel showing.

Soulis Auctions 2024. All Rights Reserved

Privacy Policy / Terms of Use

Developed & Maintained By CoreLink Development