By Jonathan Wadsworth Oriental Rug Specialist, Former Director Sotheby’s, Auctioneer, Author and Lecturer – London, England

This article supports the series of auctions dedicated to the disposal of the John Adair Jnr. Collection of Fine Caucasian and Tribal Rugs.

There is a booming global collector’s market evident today, and if considering ‘joining in’ collecting this magnificent art form, or have dipped a toe in the waters, then you will already have an appreciation of aesthetics. A collector in this field can be defined as an accumulator of rugs and larger carpets acquired specifically for decorating a home which may be eclectic or otherwise in approach or may have established a specific type or style of rug which inspires you to concentrate on. Either way, there are certain things that are worth considering to gain the most out of your enjoyment in collecting. These include how to identify a beautiful example of type and origin, the importance of colour and design, and where to gain knowledge. The history of rug weaving, and existing collector preferences can also guide a new or seasoned collector in understanding and developing an approach to meaningful and satisfying long-term collecting. There is something for all budgets in this remarkable subject of applied arts. This commentary focusses on Middle Eastern, or loosely described oriental weavings, as an historical commentary based on the considerable collector interest in this area. Though the information can in the main be applied to any area of rug or carpet collecting.

Weaving is one of the most ancient and pervasive creative activities. From the beginning of civilisation textiles have been valued the world over, embodying for many cultures the highest artistic values, and portraying countless narratives: social, spiritual, historical, technical, and commercial. Additionally, as tangible assets, rugs are portable heirlooms and generational. The term rug or carpet is far more than a floor covering in the western understanding of things, for in ancient eastern terms these single items may replace a great variety of articles such as tables, chairs, beds, coverlets and pictures. To fully understand and appreciate this remarkable art form it seems appropriate to be reminded as to what and who is involved in the creation of a woven work of art. First and foremost, what is clear is that several highly skilled individuals are required. Loom builders, wool spinners, dyers, designers, and weavers. Ultimate teamwork, appreciation and understanding of traditions and inherent artistic skills are the prerequisites for those involved. Every rug is an individual creation of an artist, (designer) and associated skilled craftsmen, and as such the artist’s vision comes to fruition following months, and often years of hard and patient work to embody the original moment of inspiration, culminating into a woven work of art mostly created by anonymous artists.

Historically, Persian Royal patronage has played a crucial part in the development of woven art. The ‘Golden’ period of Islamic art, as it is often referred developed and flourished during the period of the Safavid Empire (1501-1736), when court workshops were established under royal patronage. This, a time when great masterpieces of woven art were created. Exposure to the west was established at this time through increased trade and diplomatic interaction. Remarkably these magnificent woven treasures were made by anonymous weavers, it was only in the second half of the 19th century that recognised master weavers began to appear, identified by woven inscriptions.

Consequently, it is no surprise that rugs and carpets have for centuries been considered collectable decorative and functional artefacts. There are many esteemed historical collectors. It is known that in the 16th century, King Henry VIII owned several hundred Ottoman Turkish rugs, from evidence gained from inventories. Some of these rugs appear in his many portraits by Hans Holbein.

Consequently, it is no surprise that rugs and carpets have for centuries been considered collectable decorative and functional artefacts. There are many esteemed historical collectors. It is known that in the 16th century, King Henry VIII owned several hundred Ottoman Turkish rugs, from evidence gained from inventories. Some of these rugs appear in his many portraits by Hans Holbein.

Indeed, such lasting evidence has assisted carpet scholars in understanding the evolution of designs and the art of weaving, and thereby educating and enlightening budding collectors and art historians alike. It is generally believed that Henry VIII was often in competition with Cardinal Wolsey for gaining possession of fine examples. Such ‘historic’ collector competition in the market is of course prevalent today. Other significant collectors include Cornelius Vanderbilt, the American business magnate, William Randolph Hearst, John Rockefeller and Sigmund Freud, who’s psychoanalytical couch was famously covered with a magnificent Persian Qashqai tribal rug, supported by a mass of other beautiful colourful rugs and textiles.

From the mid- 19th century, the world of collecting was transformed. From this time the art of handmade carpet weaving underwent a significant ‘revolution’, heralding a new ‘Golden Age’ of Persian weaving referred to, and generally considered as the ‘Revival’ in Persian woven art. Designs were no longer the exclusive domain of the weaver but influenced for the first time by western intervention. This came about through increased interest amongst the rising middle classes in Europe and the United States, first initiated through the Industrial revolution in the early 19th century in the United Kingdom with an entire new class of emerging wealth. This newfound wealth was focussed on a revitalised interest in ‘all things Eastern’ which included fine carpets and textiles. Ziegler and company are a prime example, a textile company originally based in Manchester, England, set up workshops in and around Sultanabad in north Persia who, in the 1870’s through to the 1920’s produced carpets in a distinctive new style. They were primarily focussed on creating carpets with bolder more open patterns in a range of colours suited to western tastes, hitherto unseen.

From the mid- 19th century, the world of collecting was transformed. From this time the art of handmade carpet weaving underwent a significant ‘revolution’, heralding a new ‘Golden Age’ of Persian weaving referred to, and generally considered as the ‘Revival’ in Persian woven art. Designs were no longer the exclusive domain of the weaver but influenced for the first time by western intervention. This came about through increased interest amongst the rising middle classes in Europe and the United States, first initiated through the Industrial revolution in the early 19th century in the United Kingdom with an entire new class of emerging wealth. This newfound wealth was focussed on a revitalised interest in ‘all things Eastern’ which included fine carpets and textiles. Ziegler and company are a prime example, a textile company originally based in Manchester, England, set up workshops in and around Sultanabad in north Persia who, in the 1870’s through to the 1920’s produced carpets in a distinctive new style. They were primarily focussed on creating carpets with bolder more open patterns in a range of colours suited to western tastes, hitherto unseen.

At the same time ‘home grown’ Master weavers set about creating superb masterpieces in woven art based on traditional composition. A number of these master weavers are well known, and sign their work, and their weavings are highly prized in the collector and decorative furnishing markets. To name but a few, Hadji Jalili, from Tabriz, Mohtasham from Kashan, Aboul Ghasem Kermani, from Kerman. However, It is important to note that the majority of hand-made rugs and carpets are woven by anonymous weavers and still regarded outstanding works of woven art.

The furtherance of the ‘designer’ carpet can be seen in the rise of highly significant Persian Master weavers of the 1920’s, through to the 1970’s, and this is combined with the emergence of important new centres of weaving creating outstanding works of woven carpet art alongside established traditional centres. Historically, Persian Royal patronage has played a crucial part in the development of woven art. Western intervention in carpet art Revival, and significant royal patronage returned under the Pahlavi dynastic period (1925-1979). It is known that Reza Shah Pahlavi commissioned magnificent carpets from the celebrated master weavers, Amoghli, and Sabir. Their workshops were established in the 1920’s in Mashad, Khorasan. Inevitably this resulted in the setting up of increased numbers of carpet weaving workshops, not just in Khorasan, but in established traditional urban centres. In the 1930s, rugs began to appear from workshops established in Esfahan, by the Seirafian family who successfully set about creating magnificent weavings in pursuit of technical excellence, and beauty. Their rugs were duly signed and are highly prized by a discerning collector market. The increased output in carpet weaving massively increased the scope and availability for collectors to consider. It is also worth bearing in mind that rugs made around 1920 would now be considered antique. This is an aspect which can influence collector behaviour.

The furtherance of the ‘designer’ carpet can be seen in the rise of highly significant Persian Master weavers of the 1920’s, through to the 1970’s, and this is combined with the emergence of important new centres of weaving creating outstanding works of woven carpet art alongside established traditional centres. Historically, Persian Royal patronage has played a crucial part in the development of woven art. Western intervention in carpet art Revival, and significant royal patronage returned under the Pahlavi dynastic period (1925-1979). It is known that Reza Shah Pahlavi commissioned magnificent carpets from the celebrated master weavers, Amoghli, and Sabir. Their workshops were established in the 1920’s in Mashad, Khorasan. Inevitably this resulted in the setting up of increased numbers of carpet weaving workshops, not just in Khorasan, but in established traditional urban centres. In the 1930s, rugs began to appear from workshops established in Esfahan, by the Seirafian family who successfully set about creating magnificent weavings in pursuit of technical excellence, and beauty. Their rugs were duly signed and are highly prized by a discerning collector market. The increased output in carpet weaving massively increased the scope and availability for collectors to consider. It is also worth bearing in mind that rugs made around 1920 would now be considered antique. This is an aspect which can influence collector behaviour.

In broad terms rugs can be divided into two distinct groups; Weavings made in town and city workshops and those made in village workshops or woven on migration by tribal weavers.

Town and city weavings display designs that are primarily based on traditional established patterns based on or inspired by the court carpets of the 16th and 17th century. Central medallion or all over designs are present. The looms used are fixed vertical constructions. The weaver creates the pattern from a drawn cartoon resembling graph paper, each square representing one knot, prepared by a designer, creating finely drawn curvilinear patterns presenting predominantly flora forms, though animals, birds and human figures often feature in late 19th century weavings onwards. The pile is of finely spun wool or silk, or a  combination of both woven on a cotton or silk foundation. Cotton and silk foundations allow for considerable detail to be created. Significant traditional Persian urban centres weaving in this style include Esfahan, Kashan, Tabriz, Kerman, Mashad, Saruq, Malayer.

combination of both woven on a cotton or silk foundation. Cotton and silk foundations allow for considerable detail to be created. Significant traditional Persian urban centres weaving in this style include Esfahan, Kashan, Tabriz, Kerman, Mashad, Saruq, Malayer.

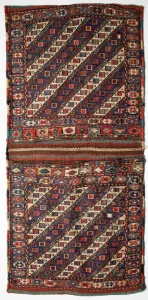

Rugs classified as ‘tribal’ stem from more ancient traditions and are classified by the tribal name or region/place of weaving. Apart from rugs, woven artefacts such as storage bags and animal trappings, are made, which form a collectable range of weavings. Their designs incorporate both bold and finely drawn geometric motifs depending on where they were made and presented in a range of organic dyes. Characteristically they depict stylised or abstract flora and fauna forms, with motifs often totemic in appearance. Designs are woven from memory with motifs passed down from generation to generation for the weaver to use in whatever way they want. As such these weavings are highly original. The pile is of wool, woven on wool and sometimes cotton foundations. They are made on horizontal looms, in home workshops or made on migration and tend to be no larger than 240cm, (8ft) in width due to space constraints and suitability for transporting if made on migration. The main areas of interest for the established collector are the Caucasus in Azerbaijan, including Kazak, Shirvan, Kuba, and related sub groups. Persian tribal groups of interest include the Qashqai, Afshar, and Kurds and related sub groups. Another significant desirable group are the Turkoman collective originating from Turkmenistan, and include sub-groups, namely the Tekke, Yomut, Salor, Saryk, and Ersari. There is also a collector focus on Baluche tribal weavings which originate from Baluchistan, Afghanistan.

In either group, it is important that a collector considers what is beautiful. Beauty is ‘in the eye of the beholder’ but as a guide there are certain principals to be considered. The composition should respond to the senses, the more you look at rugs the more your taste refines and recognises beauty. Designs should flow freely, be well balanced in scale and harmonic. The pattern elements should be easily readable whether presenting highly detailed compositions or with more open patterns. Poorly contrived designs look crowded and are hard to read, particularly when looking at urban weavings. Constant comparing and contrasting trains the eye to recognise good or not so good examples of type and origin, and is part of the ongoing learning curve for the collector.

Designs only have meaning when brought alive by colour. Naturally dyed yarns possess subtleties and nuances not generally seen in chemical (synthetic) dyestuffs. Rugs woven prior to 1880 are in the main made with colours derived from vegetation and insects. This applies to both urban, village and tribal weavings. Variations of colour created by natural dyes, gives a translucent effect almost as if looking through a stained-glass window. In addition, natural dyes don’t fade, unless exposed to lengthy periods of sunlight, so the original character of the rug is maintained over considerable time. Analine or chemical dyes began to appear from around 1860 onwards through western intervention. These colours tend to be harsh and abrasive and ‘solid’ by comparison and lack the colour variations as seen in naturally dyed weavings. The most easily identifiable synthetic colours are bright orange and purple. Both these distinctive colours began to appear from around 1870, introduced as a part of the European intervention, and were used extensively by the early years of the twentieth century. Although many weaving centres continued to use these harsh colours well into the 20th century, their lack of subtlety soon became apparent and their use quickly declined. Chemical dyes are prone to fading over time, and this invariably has a deleterious impact on appearance.

translucent effect almost as if looking through a stained-glass window. In addition, natural dyes don’t fade, unless exposed to lengthy periods of sunlight, so the original character of the rug is maintained over considerable time. Analine or chemical dyes began to appear from around 1860 onwards through western intervention. These colours tend to be harsh and abrasive and ‘solid’ by comparison and lack the colour variations as seen in naturally dyed weavings. The most easily identifiable synthetic colours are bright orange and purple. Both these distinctive colours began to appear from around 1870, introduced as a part of the European intervention, and were used extensively by the early years of the twentieth century. Although many weaving centres continued to use these harsh colours well into the 20th century, their lack of subtlety soon became apparent and their use quickly declined. Chemical dyes are prone to fading over time, and this invariably has a deleterious impact on appearance.

These days, there is a wealth of information available for collectors to help in the learning curve. The click of a ‘mouse’ in a search engine  can reveal articles, pictures, and a mass of information related to any aspect of woven art. Historically museums by very nature have always been a source of knowledge and inspiration. There is also a considerable amount of specialist and general literature available. Getting to know a specialist reputable dealer is invaluable. They will be more than happy to share their knowledge, point to relevant literature, give confidence and help you build your collection. The key is to always keep training the eye to appreciate beauty by whatever means possible. The more time put into the subject, the more satisfying and enjoyable the subject becomes.

can reveal articles, pictures, and a mass of information related to any aspect of woven art. Historically museums by very nature have always been a source of knowledge and inspiration. There is also a considerable amount of specialist and general literature available. Getting to know a specialist reputable dealer is invaluable. They will be more than happy to share their knowledge, point to relevant literature, give confidence and help you build your collection. The key is to always keep training the eye to appreciate beauty by whatever means possible. The more time put into the subject, the more satisfying and enjoyable the subject becomes.

For the collector, appreciating woven eastern art at any level involves patterns and designs which maybe repetitive and encompass meanings that we in the west cannot fully comprehend, nor mostly can they be associated with a specific artist. This does not devalue the piece. Art in whatever form presented, affects us on a humanist, universal level and will satisfy visually and viscerally. In woven art this satisfaction is achieved through colour and its relationships, defined by forms and modified by texture. Immersing in this magnificent art form will give a lifetime of pleasure for sure, as certainly embraced by John Adair Jnr., along with many others.

whatever form presented, affects us on a humanist, universal level and will satisfy visually and viscerally. In woven art this satisfaction is achieved through colour and its relationships, defined by forms and modified by texture. Immersing in this magnificent art form will give a lifetime of pleasure for sure, as certainly embraced by John Adair Jnr., along with many others.

Soulis Auctions 2024. All Rights Reserved

Privacy Policy / Terms of Use

Developed & Maintained By CoreLink Development